SIMPLY BELIZE: A Cultural Diary

EPISODE: # 2 - Mopan Maya

DURATION: 30 minutes

DATE AIRED : 12/3/2002

|

HOST:

Hello and welcome to episode two of SIMPLY BELIZE - A Cultural Diary! I'm Curtis Gillett and tonight we'll meet the Mopan Mayas of Belize.

Now the Mopan Mayas are a people traditionally found south of the Mopan River in the villages of western and southern Belize. But there was a time not too long ago when approximately 23 different groups of Mayas inhabited a central area of land in Mesoamerica called the Mundo Maya.

This Mayan world included what is today the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico, the entire country of Belize and parts of Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras.

Within this Mundo Maya, the ancient Mayas farmed their milpas, practiced their religion, and traveled freely.

NO BOUNDARIES

DIEGO BOL (Teacher, Toldeo Community College):

DIEGO BOL (Teacher, Toldeo Community College):

Prior to the coming of the Europeans there was no boundary. The Mayas did not know anything about boundary. No Guatemala, Belize existed at that time. So we cannot say that part of the Mopan Maya were living in Belize or part of the Maya were living in Guatemala. It was one big Maya World. But when the Europeans came, they put in boundaries. They divided the Maya land.

HOST:

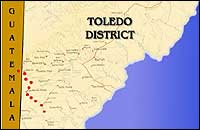

The first Europeans to arrive in the Maya World came from Spain with their first stop being Mexico's Yucatan peninsula in 1519. A few years later, in 1525, the Spanish conquistador, Hernan Cortez marched from Mexico through the interior of Central America, in search of new lands and people to conquer. Cortez's journey took him through the southwest corner of what is now Belize's Toledo district, a low-lying humid jungle inhabited by Mayas in scattered settlements.

DIEGO BOL:

There are quite a number of documents that I have come across that stated that the Manche Chol and the Mopan Maya occupied the southern portion of what we call today, Belize. That is from the Sittee River down to the Sarstoon.

There are quite a number of documents that I have come across that stated that the Manche Chol and the Mopan Maya occupied the southern portion of what we call today, Belize. That is from the Sittee River down to the Sarstoon.

When Cortez came in the 1500s and skirted along the coast of what we call now today, Belize, he did mention about sighting or coming across some native peoples.

HOST:

Cortez's reports later encouraged the Spanish authorities from the villa of Bacalar, a northern town established around 1544, to head south and spread the Catholic doctrine.

DIEGO BOL:

The Spaniards began Christianizing the Mayas. And the Mayas, some of them refused to be Christianized and some of them then decided to run away into the deep recesses of the forests. These people that ran away from Christianity, the Mopan Maya call them "Che'il" and the Q'eqchi' call them "Ch'olwinq".

HOST:

"Che'il" literally translated means "those that ran away". They ran away into the Maya Mountain range with determined efforts to hold onto life as they knew it, or more to the point, to escape the barbarity of the Spaniards. Once inside the mountain range, the "Che'il"were swallowed up by the jungle but there are some who believe the "Che'il" are still there.

DIEGO BOL:

There are stories about these Maya workers who logged in the area that is behind San Jose right now. And they used to talk about seeing little children on their picado, but as they come close those little children would disappear. And they still consider them as the "Che'il" that run away. So they have that story about the presence of the Mayas in the jungle even up to today.

HOST:

The Mopans who stayed behind were forced to convert to Christianity, often under threat of torture. To make matters worse, they were then rounded up like cattle and moved to more centralized villages such as San Luis in the Peten region of Guatemala where they lived on "ecomiendas."

ANGEL CAL (President, University of Belize):

An "encomienda" is a village of Mayan people that is entrusted to a Spaniard. The Maya of that village have to provide tribute to the Spaniard and the Spaniard's responsibility was to protect the village and to "Christianize" the people who lived there.

An "encomienda" is a village of Mayan people that is entrusted to a Spaniard. The Maya of that village have to provide tribute to the Spaniard and the Spaniard's responsibility was to protect the village and to "Christianize" the people who lived there.

HOST:

Forced to live under these conditions could not have been easy and so it was only natural for the Mayas to rebel. For more than a century, the Mayas kept up an active resistance against the Spaniards and in 1638 burnt all their churches in Southern Belize to the ground. Frustrated, the Spaniards withdrew from Belize for more than 50 years. But they would be back.

Spurred on by their 1697 victory over the Itza Mayas of Peten, the Spanish returned to Belize in 1707 to defeat TIPU - the last major Maya town, west central of Belize. They moved all the residents to San Luis Peten in Guatemala, leaving behind an abandoned settlement.

But the Spaniards were not the only Europeans to change Mayan lives. The British, even without religious zeal, were just as threatening.

VALENTINO SHAL (President, Toledo Maya Cultural Council):

Most, if not all of the contacts with the British by the Mayas, were not friendly. Well that is totally understandable because of the attitude the British had towards Mayas and the Mayan territory.

Most, if not all of the contacts with the British by the Mayas, were not friendly. Well that is totally understandable because of the attitude the British had towards Mayas and the Mayan territory.

Traditionally the Mayas saw the land as free and not a commodity to be bought and sold because it provided them with everything they needed for their lives. The British saw it in a different way. They saw it as a means of commodity where they could trade and sell and produce that kind of wealth for themselves.

HOST:

The British woodcutters were interested in the land for the valuable timber it provided. So the Mayas living on the land were seen as obstacles and needed to be removed.

VALENTINO SHAL:

They were the ones who established the reservation system in Toledo so that the Mayas would leave them alone and so that the Mayas would have their own territory within which to work. They were established around 1844. I think mostly to pacify the Mayas; to prevent them from having any further conflicts with the British.

But it was done mainly to serve British interests and not Mayan interests.

RE-ENTRY?

HOST:

In 1707, the Spaniards had forcibly removed the Mayas at TIPU to Lake Peten Itza in Guatemala, but in the 1880s, a group of Mopan Mayas, on their own, returned to Belize.

In 1707, the Spaniards had forcibly removed the Mayas at TIPU to Lake Peten Itza in Guatemala, but in the 1880s, a group of Mopan Mayas, on their own, returned to Belize.

DIEGO BOL:

In 1886 about a hundred families from San Luis, Peten re-enter Belize, what we call today. Belize. And they settled at Pueblo Viejo. However they were not secure. They didn't feel secure because it was close to the Guatemalan border. And they were running away from forced labour.

HOST:

During the 1800s and well into the 1900s indigenous Maya people suffered under the Guatemalan military. The lands they used for traditional farming were sold to foreigners, they were not provided with any medical services and to make matters worse, they were forced to join the Guatemalan military and secure the borders against the British in Belize.

DIEGO BOL:

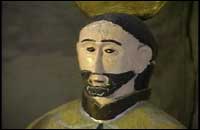

So they run away and they entered back into Belize and they settled at Pueblo Viejo. They started their farming and they were not getting as good a crop as they did in San Luis. And they thought it was because they did not bring their saint…or their god.

So, they did make an effort to go back for the god. That is what they call now the San Luis, the San Luis Rey.

(The following story was told in Mopan Maya with English subtitles)

MAURICIO AH (Mopan Farmer):

After awhile, they started to get sick and so they decided to go back for their saints.

They believed that the sickness would come to an end if they brought their saint back.

They believed that the sickness would come to an end if they brought their saint back.

One night they returned to San Luis and headed straight for the church. They took 3 statues and 3 bells.

Afterwards they realized that what they had done was wrong and that the people of San Luis would come looking for their saints.

So they wrote the Governor telling him about a possible attack and asked for some assistance.

The men of San Luis did come and began causing problems but the men of San Antonio arrested the troublemakers.

They were later released after promising never to come back to San Antonio

And that's the story of the Mayas.

HOST:

The 3 original statues have since perished in mysterious fires that destroyed first a thatch and then a wooden church. Luckily the mayordomo of the village - an elder in charge of the statue - had a photo and a new San Luis Rey was made.

The 3 original statues have since perished in mysterious fires that destroyed first a thatch and then a wooden church. Luckily the mayordomo of the village - an elder in charge of the statue - had a photo and a new San Luis Rey was made.

Most Mopan Mayas will tell you they are Roman Catholics. But even now they still retain some of their ancient Mayan traditions.

HOST:

The term I like to use is the word syncretism.

The Mopan Mayas, they believe in the Catholic faith, right, but they still pray to their god. For example, they still pray to the god of corn. They still pray to the god of the forest. They still pray to the god of the caves, the rocks. And even though they might be using Christian symbols, like the Blessed Virgin Mary or like San Luis Rey, the patron Saint, yet when they pray to these gods they still have in their minds, their gods of corn like "Yun Kax" or their god of the forest, like "Chaak" the god of thunder. They still pray to those gods.

So the Catholics were not able to actually remove that from them. But they have learned to live with it.

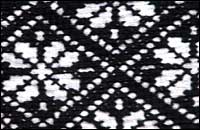

MOPAN MAYA EMBROIDERY

HOST:

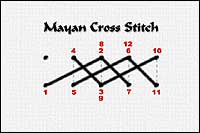

Traditional Mopan Maya embroidery is done using black thread on a white background. They are geometric designs sewn with a complicated cross-stitch.

Regular cross stitching appears as a simple X. but in Mopan embroidery, the X's of the cross-stitch tends to overlap each other. This allows the thread to cover the background completely, leaving a clear pattern to emerge from the white cloth. Sometimes this style is reversed. And the black thread is used to cover the pattern leaving the white background untouched.

Regular cross stitching appears as a simple X. but in Mopan embroidery, the X's of the cross-stitch tends to overlap each other. This allows the thread to cover the background completely, leaving a clear pattern to emerge from the white cloth. Sometimes this style is reversed. And the black thread is used to cover the pattern leaving the white background untouched.

But before any sewing is done, it is very important to make sure that you have the right cloth. If the weave is uneven, the delicate pattern will be distorted.

DONATILA CHUN:

This stitch is something like mathematics. So I have to make sure all my lines are balanced, so that when I start to do my work it won't go crooked.

This stitch is something like mathematics. So I have to make sure all my lines are balanced, so that when I start to do my work it won't go crooked.

HOST:

Donatila Chun is a Mopan Mayan woman who promotes Mayan arts and craft from her booth at the Marine Terminal in Belize City. She is originally from San Antonio, Toledo.

DONATILA CHUN:

As a child we had to learn these work. You're a girl. You have to learn these work.

HOST:

It's not an easy job. Sewing such intricate patterns can take up to several weeks to complete.

DONATILA CHUN:

You have to use a lot of your brain when you're doing this. It's just like mathematics. You cannot go wrong. Cause if you go wrong you have to rip your work. And I don't like to rip.

You have to use a lot of your brain when you're doing this. It's just like mathematics. You cannot go wrong. Cause if you go wrong you have to rip your work. And I don't like to rip.

HOST:

Mopan women have created many patterns that are influenced by their natural environment. It is typical to see birds, animals and trees on embroidery strips.

DONATILA CHUN:

They have their own way of imagining this animal. And they will have to find out how many stitch they have to put on the cloth. Then later on, then they would transfer it to another pattern that they would keep it. They would keep that so it would not [get] lost like if you were putting a design on a paper, it wouldn't get mash or get destroyed or anything. But on the cloth it would last forever. So that's the way the Mayan women preserve their patterns.

They have their own way of imagining this animal. And they will have to find out how many stitch they have to put on the cloth. Then later on, then they would transfer it to another pattern that they would keep it. They would keep that so it would not [get] lost like if you were putting a design on a paper, it wouldn't get mash or get destroyed or anything. But on the cloth it would last forever. So that's the way the Mayan women preserve their patterns.

If I would want a pattern, my aunt or my, my sister-in-law would want, I would go and borrow. We borrow from each other.

MOPAN MAYA

DRESS CODES

HOST:

It is very difficult to find Mopan men in Belize who still wear traditional clothing today. Mostly it is the women in typical dress.

It is very difficult to find Mopan men in Belize who still wear traditional clothing today. Mostly it is the women in typical dress.

Little girls wear a cotton dress with narrow strips of embroidery around the neck and arms. And the patterns on their embroidery are mainly that of small animals like baby chickens and flowers.

HOST:

As they become young women, the simple dress is exchanged for a blouse with wider more elaborate strips of embroidery and a colorful skirt with frills around the midsection and the bottom. The bright colors and many frills are there for a reason - to attract would-be husbands.

As they become young women, the simple dress is exchanged for a blouse with wider more elaborate strips of embroidery and a colorful skirt with frills around the midsection and the bottom. The bright colors and many frills are there for a reason - to attract would-be husbands.

Grandmothers wear a similar outfit, except now the neckline is square, the embroidery even more elaborate and wider and the frills from the midsection are now gone.

DONATILA CHUN:

From way back as a child growing up this was the way they dressed when culture was strong. And as you see them visiting the various villages in the past you can identify them "Oh, she come from a, a certain village…San Antonio, Pueblo Viejo, San Jose and all those villages…Santa Cruz, Santa Elena…those are the Mopan Mayan villages so you can see, you can identify them right away by their clothes

HOST:

But times are changing in Belize and young women no longer want to wear traditional clothing. Interestingly, it is mostly the men who complain.

But times are changing in Belize and young women no longer want to wear traditional clothing. Interestingly, it is mostly the men who complain.

MAURICIO AH:

Few months ago, I met one of my Mayan friend whe start to tell me, "Do you know what's going on in our hometown, in San Antonio." I said "Like what?" He said "our girls and the women, they want to, they're changing their style. Yes. But to me, I don't want like that. It's very wrong to me.

GREGORIO CHIAC (Alcalde, San Antonio):

Like you see these ladies in this big dress. You see this. Not even my wife, she don't want that again. So we only have maybe a few of these. After these pass away, well maybe we won't find no ladies with dress like that again.

Like you see these ladies in this big dress. You see this. Not even my wife, she don't want that again. So we only have maybe a few of these. After these pass away, well maybe we won't find no ladies with dress like that again.

HOST:

Even the colors of the embroidery are changing.

DONATILA CHUN:

A lot of us, including myself, I look at it as a part of art and it's something that it can change. Because all around us, it's colourful, like in technicolour. You have green, red; it's not black and white, like in the olden times, black and white photographs. No, we can change it.

GIVE MY PEOPLE A CHANCE

DIEGO BOL:

After I have finished my high school, I wanted to pursue a profession. I wanted to be a lawyer. Unfortunately I didn't have the money so I was going to look for a scholarship. When I went to the officials in Belize City and asked for a scholarship and I told them that I wanted to be a lawyer, a Maya lawyer. They asked me, "What about the Maya? The Maya does not need any lawyers."

That was in the 60's I mentioned about the 60's, no, the 70's. Now coming into the 80s things began to change. An organization called the Toledo Maya Cultural came into being. And this organization began fighting for the rights of the indigenous people in southern Belize.

DONATILA CHUN:

Sometimes in the past they give us raw name like "Ingin." Things weh I… you know I am a person that like to do my research. I like to go to the libraries. I read and I no see the reason why they call us Indians because we don't come from India and we don't speak Indian language. We don't even look like Indians.

DIEGO BOL:

They began fighting for the rights of the Mayas to an education based on their ability and not based on whether you are a Mopan or a Mestizo.

Then they began talking about the educating the people about the work of our ancient ancestors, The Mayan temples that we have today.

SANTIAGO COC (Park Warden, Lubaantun):

The center of Lubaantun consists of five layers of construction so it was one on top of the other.

DIEGO BOL:

They began talking to them about developing pride. And at the same time indicating to them that education does not mean that you cannot go back and do your farm work.

They began talking to them about developing pride. And at the same time indicating to them that education does not mean that you cannot go back and do your farm work.

HOST:

Reconciling the traditional with the modern is never easy, especially in the face of racial prejudice and social pressure to adapt to non-Mayan ways of life.

DONATILA CHUN:

Well you know the young people travel a lot now, more than the older folks as again culture changes. And when culture begin to change, they tend to look at their culture as something old and get tired of it and they want start try something new. And then they begin to buy ready-made clothes and then they don't look like indigenous people or Maya people anymore.

And then the city people would call them "you Spanish" or "you alien" and you know, the different names. And then this becomes a question, "what are you, why are you calling me 'alien' or why are you calling me 'Spanish' and I know I'm a Maya."

VALENTINO SHAL (President, Toledo Maya Cultural Council):

As Belizeans now, the Mayas I think, the Mopan Mayas are asserting their right to different things as equal to that of any other citizen. And so as we continue to develop and to change, certain things about our culture would change. It would none-the-less effect what the Belizean culture is and how the Belizean culture is defined.

HOST:

I'm Curtis Gillett and you've been watching SIMPLY BELIZE: A Cultural Diary.

Click here for more photos

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()